The Certainties: More Inflation … and Higher Taxes

What The Scale Of ‘Bad’ Fiscal Dynamics Will Mean For Asset Allocation

Source: X @Kathleen_Tyson_

Get used to it. US ‘taxes’ have already de facto risen by a staggering 38% since 2019: at least, according to Milton Friedman’s rule all government outlays are taxes, whether collected directly through the IRS or indirectly via faster future inflation. But whatever the nuances, public spending across the World has jumped higher since both the 2008/09 GFC and COVID and, what’s more, stayed high, while tax revenues are broadly flat as a share of GDP. This is a new World of ‘big government’. In short, primary public deficits are already sky high and with public debt to GDP ratios rising, the interest bill ratchets ever higher, thereby compounding the fiscal crisis by piling on more-and-more public debt.

Worryingly, history shows this is entirely sustainable. Take Japan, which is around a generation ahead of the West, but becoming ever more indebted. Japanification a period of high debts, sluggish growth and ageing demographics is spreading from the East. In her attempts to de-lever her economy, Japan has only managed to shift the debt burden from the private to the public sector, but overall debt has still grown faster than GDP.

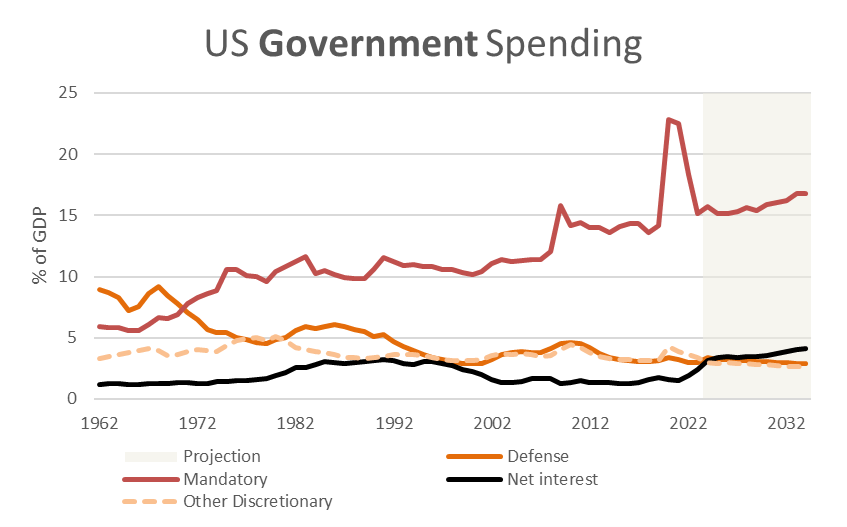

Evidence also the latest US CBO (Congressional Budget Office) Budget Projections for 2024-34 published in mid-2024. These show a worrying drift higher in both mandatory outlays (e.g. Social Security and Medicare) and interest payments, plus an unconvincing flat-lining in Defense and other discretionary spending. Social Security and Medicare are likely off-limits for politicians to reform, while Defense has its own dynamics and interest charges are math. Consider how US defense outlays averaged 8.4% of US GDP in the Cold War era of the 1960s and a lesser 5.6% in the more benign 1980s. They are projected to average an unlikely 3% over the next decade, whereas 5% of GDP seems a more appropriate target. What’s more, recessions have tended to add at least 3-5% of GDP to the deficit, and they are not accounted for in these CBO estimates.

Extrapolating these projections out a further 20 years warns that, by around 2050, US public sector outlays could make up one-third of GDP, compared to under a fifth in the late-1960s. Correspondingly, the US gross public debt to GDP ratio is slated to climb ever higher reaching 175% of GDP by 2050. The arithmetic detailed in the following table is hard to deny.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Capital Wars to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.